HAT-trie, a cache-conscious trie

Tries (also known as prefix trees) are an interesting beast. A Trie is a tree-like data structure storing strings where all the descendants of a node share a common prefix. The structure allows fast prefix-searches, like searching for all the words starting with ap, and it can take advantage of the common prefixes to store the strings in a compact way.

Like most trees, the problem with the main implementations of tries is that they are not cache-friendly. Going through each prefix node in a trie will probably cause a cache-miss at each step which doesn’t help us to get fast lookup times.

In this article we will present the HAT-trie1 which is a cache-conscious trie, a mix between a classic trie and a cache-conscious hash table.

You can find a C++ implementation along with some benchmarks comparing the HAT-trie to other tries and associative data structures on GitHub.

In the next sections, we will first explain the concept of trie more thoroughly. We will then explain the burst-trie and the array hash table, some intermediate data structures on which the HAT-trie is based. We then finish with the HAT-trie itself.

Trie

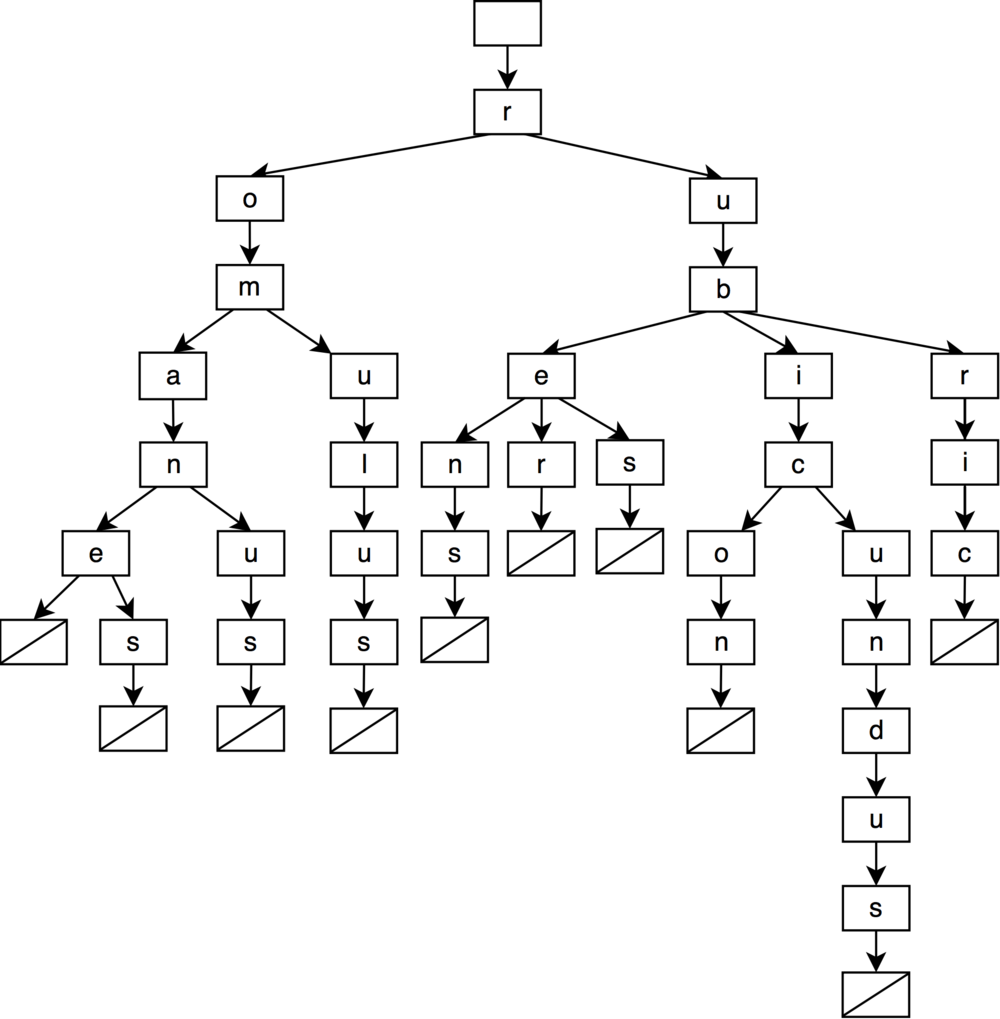

A trie is a tree where each node has between 0 and | Σ | children, where | Σ | is the size of the alphabet Σ. For a simple ASCII encoding, each node will have up to 128 children. With UTF-8 we can break down a character into its 8-bits code units and store each code unit in its own node which would have up to 256 children. The Greek α character which takes two octets in UTF-8, 0xCEB1, would be stored in two nodes, one for the 0xCE octet and one child node for the 0xB1 octet.

All the strings which are descendants of a node share the node and its ancestor as common prefix.

A leaf node, which has no child, marks the end of a string.

Let’s illustrate all this with some figures. We will use the following words in our examples:

- romane

- romanes

- romanus

- romulus

- rubens

- ruber

- rubes

- rubicon

- rubicundus

- rubric

Which will give us the following trie.

When we want to search for all the words starting with the roma prefix, we just go down the tree until we match all the letters of the prefix. We then just have to take all the descendants leafs of the node we reached, in this example we would have romane, romanes and romanus.

The implementation itself would just look like a k-ary tree.

To store the children, we can use an array of size | Σ | (let’s say 128, we only need to support the ASCII encoding in our example). Fast but not memory efficient (a sparse array/sparsetable can reduce the overhead with some slowdown).

class node {

// array of 128 elements, null if there is no child for the ASCII letter.

node* children[128];

};

One common way to reduce the memory usage while still using an array is to use the alphabet reduction technique. Instead of using an alphabet of 256 characters (8 bits), we use an alphabet of 16 characters (4 bits). We then just have to cut the octet in two nibbles (4 bits) and store two parent-child nodes (same as described above with the UTF-8 code units). More compact but longer paths in the tree (and thus more potential cache-misses).

Another way is to use a simple associative container mapping a character code unit to a child node. A binary search tree or a sorted array if we want to keep the order, or eventually a hash table otherwise. Slower but more compact even if the alphabet is large.

class node {

// C++

// Binary search tree

std::map<char, node*> children;

// Hash table

// std::unordered_map<char, node*> children;

// Sorted array

// boost::flat_map<char, node*> children;

// Java

// Binary search tree

// TreeMap<char, node> children;

// Hash table

// HashMap<char, node> children;

};

We can also store the children in a linked list. The parent has a pointer to the first child, and each child has a pointer to the next child (its sibling). When then have to do a linear search in the list to find a child. Compact but slow.

class node {

char symbol;

node* first_child;

node* next_sibiling;

};

Note that we use empty nodes to represent the end of a string in the figures as visual marker. An actual trie implementation could use a simple flag inside the node containing the last letter of a string to mark its end.

Compressed trie

Reducing the size of a node is important, but we can also try to reduce the number of nodes to have a memory efficient trie.

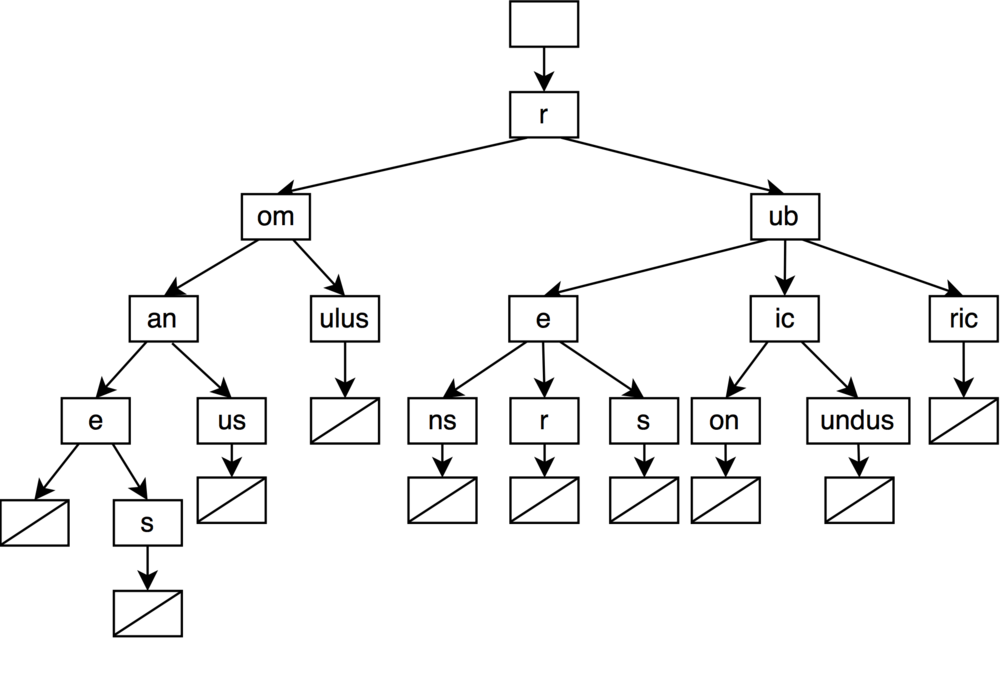

You may have noticed that in the previously exposed trie, some nodes just form a linked list that we could compress. For example the end of the word rubicundus is formed by the chain u -> n -> d -> u -> s. We could compress this chain into one undus node instead of five nodes.

The idea of compressing these chains has been used by a lot of trie based data structures. They will not be detailed here as it would be too long, but if you are interested you may look into radix tries, crit-bit tries and qp tries.

Now that we know the basic concept of a trie, let’s move to the burst-trie.

Burst-trie

A burst-trie2 is a data structure similar to a trie but where the leafs of the trie are replaced with a container which is able to store a small number of strings efficiently. The internal nodes are normal trie nodes (in the following figures we will use an array to represent the pointers to the children).

The container itself may vary depending on the implementation. The original paper studies the use of three containers: a linked list (with an eventual move-to-front policy on accesses), a binary search tree and a splay tree (which is a self-balancing binary search tree where frequently accessed nodes are moved close to the root).

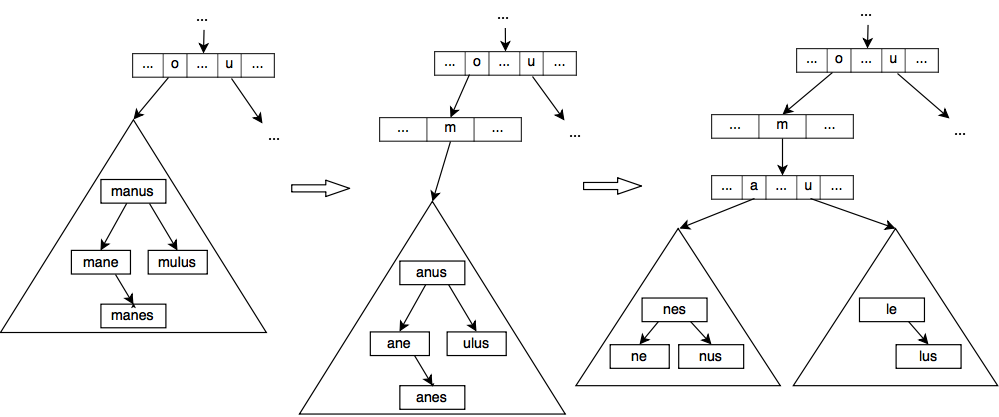

The burst-trie starts with a single empty container which grows when new elements are inserted in the trie until the container is deemed inefficient by a burst heuristic. When this happen, the container is burst into multiple containers

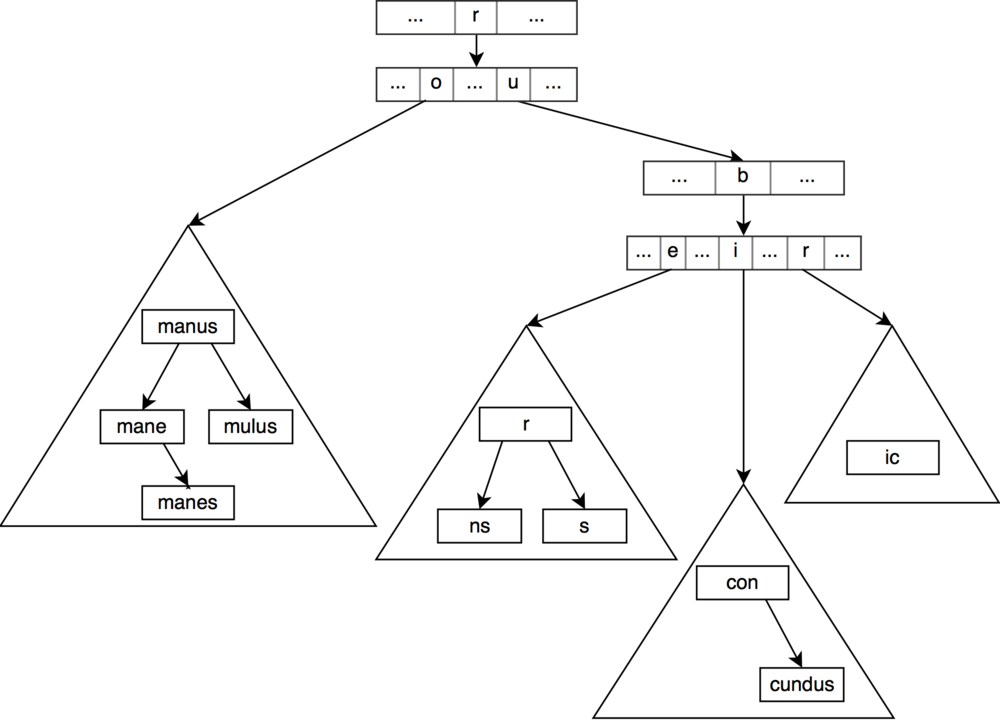

During the burst of a container node, a new trie node is created to take the spot of the container node in the tree. For each string in the original container, the first letter is removed and the rest of the string is added to a new container which is assigned as child of the new trie node at the position corresponding to the removed first letter. The process recurses until each new container satisfies the burst heuristic.

The burst heuristic which decides when a container node should be burst can vary depending on the implementation. The original paper proposes three options.

- Limit. The most straightforward heuristic bursts the container when the number of elements in the container is higher than some predefined limit L.

-

Ratio. The heuristic assigns two counters to each container node. A counter N which is the number of times the container has been searched and a counter S which is the number of searches that ended successfully at the root node of the container, i.e. a direct hit. When the ration S/N is lower than some threshold, the container is burst.

The heuristic is useful when a move-to-root approach on lookups is used, as in the the splay tree, combined with skewed lookups (some strings have more lookups than others).

-

Trend. When a container is created a capital C is allocated to the container node. On each successful access, the capital is modified. If the access is a direct hit, the capital is incremented with a bonus B, otherwise the capital is decremented by a penalty M. A burst occurs when the capital reaches 0.

As with the ratio heuristic, the heuristic is useful with a move-to-root approach and skewed lookups.

Array hash table

An array hash table3 is a cache-conscious hash table specialized to store strings efficiently. It’s the container that will be used in the burst-trie to form a HAT-trie.

A hash table is a data structure which offers an average access time complexity of O(1). To do so, a hash table uses a hash function to maps its elements into an array of buckets. The hash function, with the help of a modulo, associates an element to an index in the array of buckets.

uint hash = hash_funct("romulus"); // string to uint function

uint bucket_index = hash % buckets_array_size; // [0, buckets_array_size)

The problem is that two keys can end-up in the same bucket (e.g. if hash_funct("romulus") % 4 == hash_funct("romanus") % 4). To resolve the problem, all hash tables implement some sort of collisions resolution.

One common way is to use chaining. Each bucket in the buckets array has a linked list of all the elements that map into the bucket. On insertion, if a collision occurs, the new element is simply appended at the end of the list.

For more information regarding hash tables, check the Wikipedia article as this is just a quick reminder.

The main problem of the basic chaining implementation is that it’s not cache-friendly. In C++, if we use a standard hash table of strings, std::unordered_map<std::string, int>, every node access in the list requires two pointers indirections (only one if the small string optimization can be used). One to get the next node of the list and one to compare the key.

In addition to the potential cache-misses, it also requires to store at least two pointers per node (one to the next node, and one to the heap allocated area of the string). It can be a significant overhead if the strings are small.

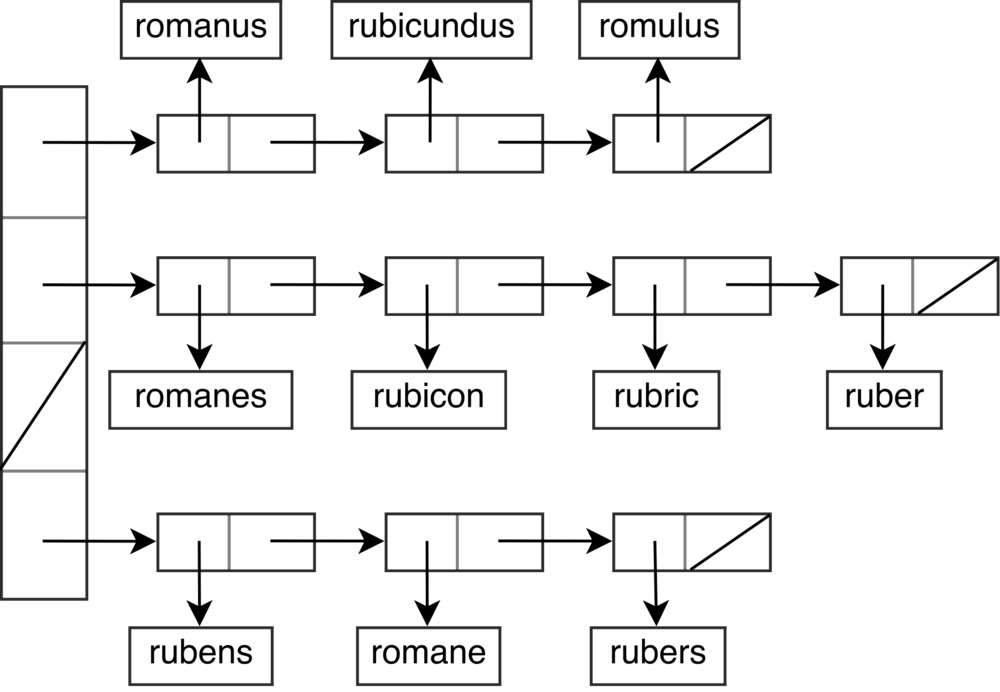

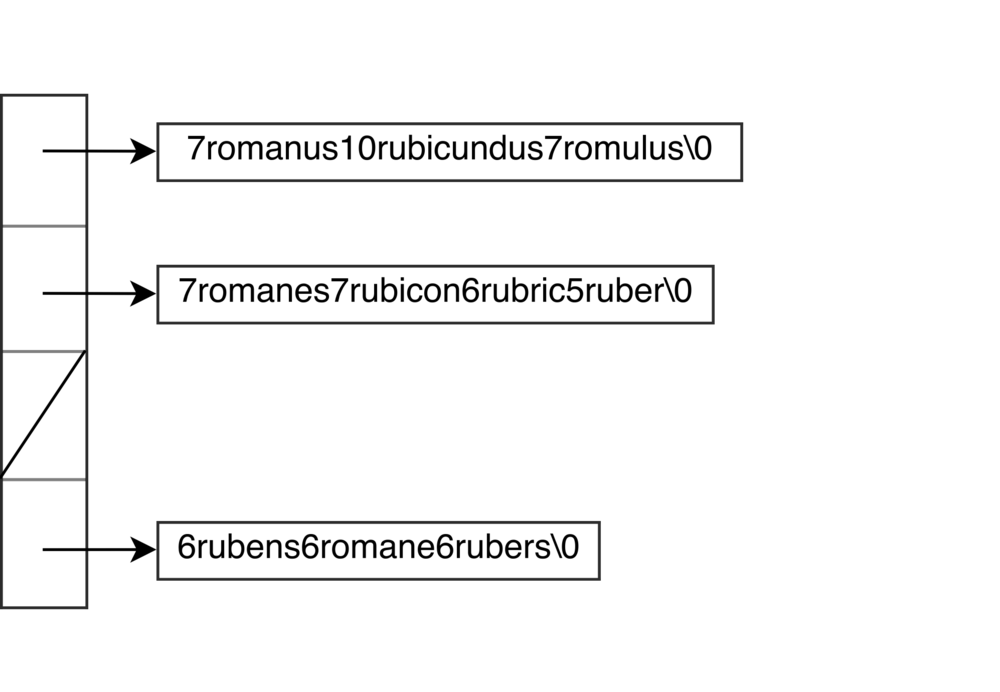

The goal of the array hash table is to alleviate these inconveniences by storing all the strings of a bucket in an array instead of a linked list. The strings are stored in the array with their length as prefix. In most cases, we will only cause one pointer indirection (more if the array is large) to resolve the collisions. We also don’t need to store superfluous pointers reducing the memory usage of the hash table.

The drawback is that when a string needs to be appended at the end of the bucket, a reallocation of the whole array may be needed.

The array hash table provides an efficient and compact way to store some strings in a hash table. You can find the C++ implementation used by the HAT-trie on GitHub.

HAT-trie

Now that we have all the building blocks for our HAT-trie, let’s assemble everything.

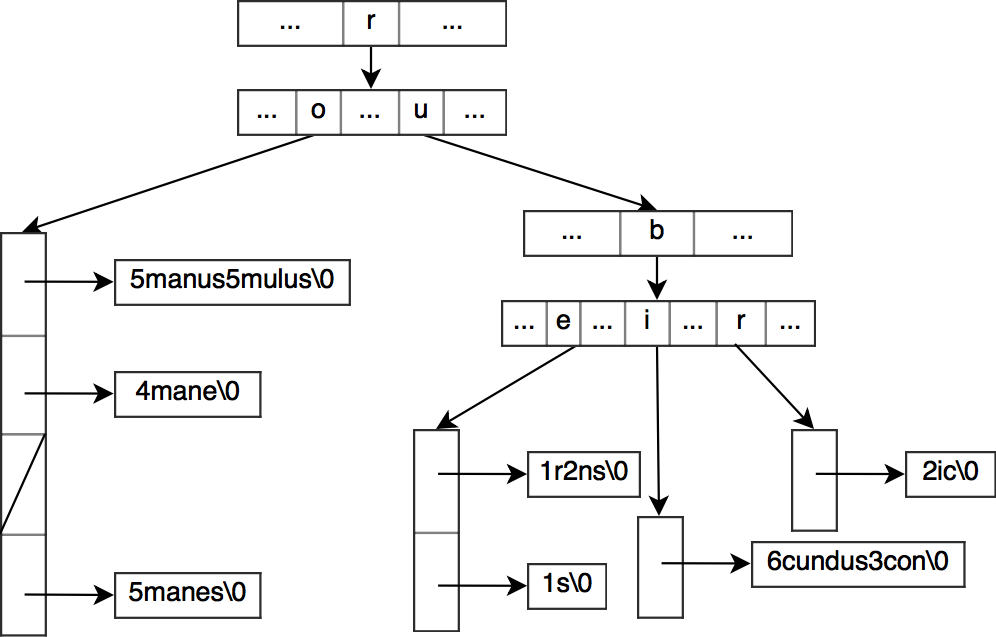

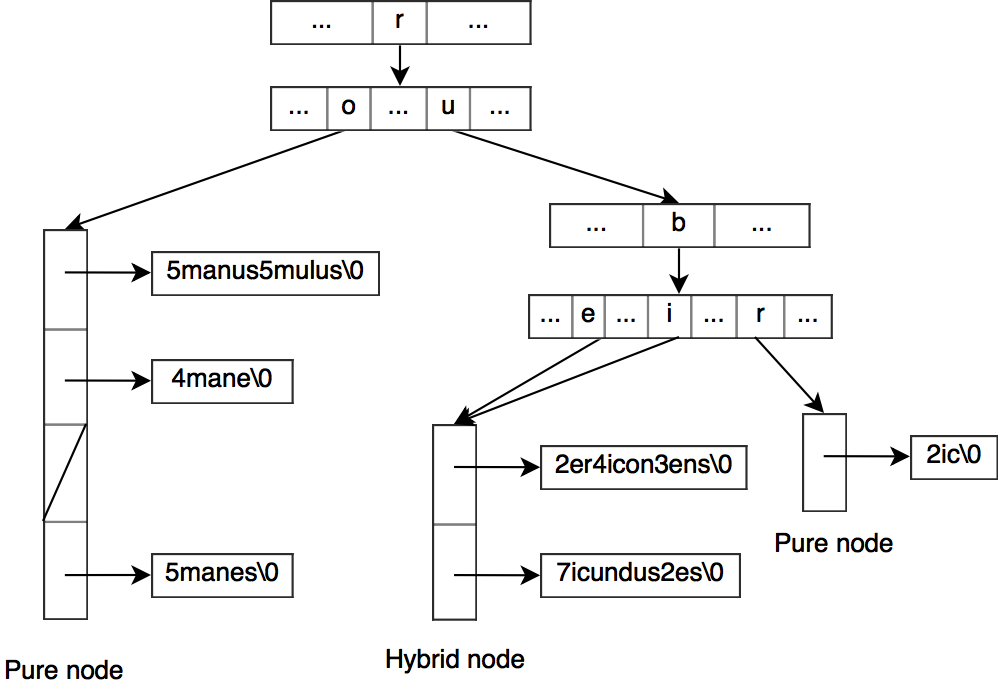

The HAT-trie is essentially a burst-trie that uses an array hash table as container in its leaf nodes.

As with the burst-trie, a HAT-trie starts with an empty container node which is here an empty array hash table node. When the container node is too big, the burst procedure starts (the limit burst heuristic described earlier is used in the HAT-trie).

Two approaches are proposed by the paper for the burst.

-

Pure. In a way similar to the burst-trie, a new trie node is created and takes the spot of the original container node. The first letter of each string in the original container is removed and the rest of the string is added to a new array hash table which is assigned as child of the new trie node at the position corresponding to the removed first letter. The process recurses until the new array hash tables sizes are below the limit.

-

Hybrid. Unlike a pure container node, a hybrid container node has more than one parent. When we create new hybrid nodes from a pure node, we try to find the split-letter that would split the pure node the most evenly in two. All the strings having a first letter smaller than the split-letter will go in a left hybrid node and the rest will go in the right hybrid node. The parent will then have its pointers for the children corresponding to a letter smaller than the split-letter point to the new left hybrid node, the rest to the right hybrid node. Note that unlike the pure node, we keep the first letter of the original strings so we can distinguish from which parent they come from.

If we are bursting a hybrid node, we don’t need to create a new trie node. We just have to split the hybrid node in two nodes (potentially pure nodes if the split would result for a node to only have one parent). and reassign the children pointers in the parent.

Using hybrid nodes can help to reduce the size of the HAT-trie.

A HAT-trie may contain a mix of pure and hybrid nodes.

The main drawback of the HAT-trie is that the elements are only in a near-sorted order as the elements in the array hash table are not sorted.

The consequence is that on prefix lookups we may need to do some extra work to filter the elements inside an array hash table node.

If we are searching for all the words starting with the ro prefix, things are easy as going down the tree leads us to a trie node. We just have to take all the words in the descendants of the trie node.

Things get more complex if we are looking for the words having roma as prefix. Going down the tree gets us to a container node while we still have the letters ma to check for our prefix. There is no guarantee that the suffixes in the container node will have the ma letters as prefix (e.g. mulus suffix), we need to do a linear filtering. But as the maximum size of the array hash table is fixed, the complexity of the prefix search remains in O(k + M), where k is the size of the prefix and M is the number of words matching the prefix, even if we have millions of strings in our HAT-trie. We just have a higher constant factor which depends on the maximum size of the array hash table.

Another consequence of this near-sorted order is that if we want to iterate through all the elements in a sorted order, the iterator has to sort all the elements of the container node each time it hits a new container node. As the maximum size of a container node is still fixed, it shouldn’t be too bad, but other structures may be a better fit if the elements need to be sorted.

In the end the HAT-trie offers a good balance between speed and memory usage, as you can see in the benchmark, by sacrificing the order of the elements for a near-sorted order instead.

References

-

Askitis, Nikolas, and Ranjan Sinha. “HAT-trie: a cache-conscious trie-based data structure for strings.” Proceedings of the thirtieth Australasian conference on Computer science-Volume 62. Australian Computer Society, Inc., 2007. ↩

-

Heinz, Steffen, Justin Zobel, and Hugh E. Williams. “Burst tries: a fast, efficient data structure for string keys.” ACM Transactions on Information Systems (TOIS) 20.2 (2002): 192-223. ↩

-

Askitis, Nikolas, and Justin Zobel. “Cache-conscious collision resolution in string hash tables.” International Symposium on String Processing and Information Retrieval. Springer Berlin Heidelberg, 2005. ↩